A Brief Literature Review of Black Community Development Financing

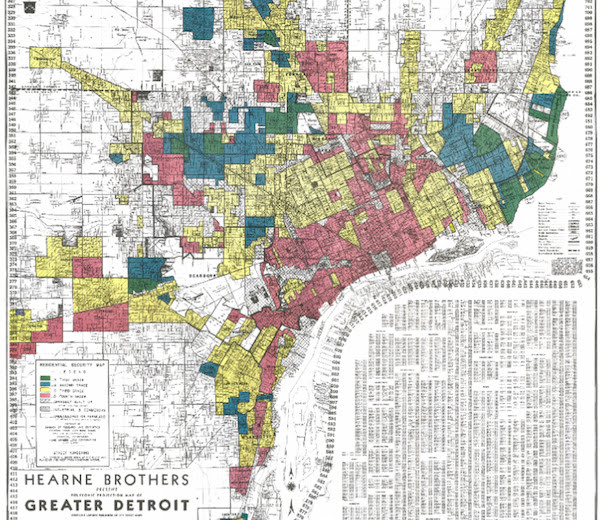

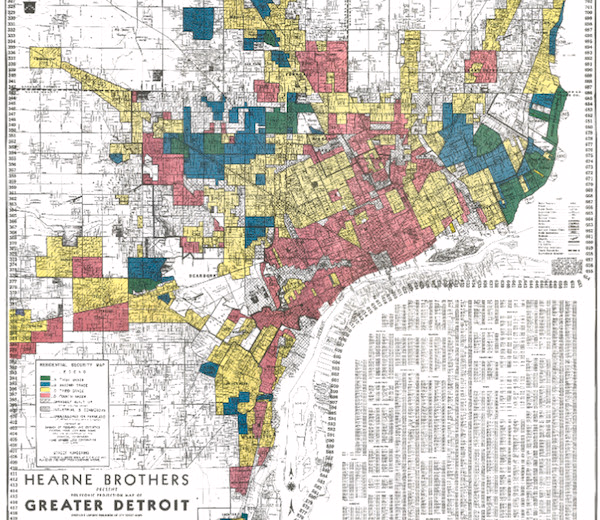

During the mid-twentieth century, the United States segregated cities and excluded Black Americans from wealth building through redlining and exclusionary housing practices. In 1933, the Federal Housing Administration began to subsidize developers who built suburban homes in communities designated for whites only[1]. Furthermore, they insured loans made for homes in white neighborhoods yet refused to insure mortgages in and near Black neighborhoods – a practice known as redlining[2]. This capital disparity left drastic effects on the landscape of our country, and resulting racial and economic segregation persists in our communities to this day. These racist policies and systems excluded African Americans from wealth generation. According to The Color of Law[3] author Richard Rothstein, this state-sponsored system of segregation drove a wedge in the racial wealth gap. African American wealth makes up just 5% of the wealth of white families. Because most families make up their wealth through homeownership, Rothstein says, “this enormous difference is almost entirely attributable to federal housing policy in the twentieth century.” As of 2019, Black household wealth is only 12.7%[4] the wealth of white households according to the National Advisory Council on Eliminating the Black-White Wealth Gap — a panel of 10 national experts in economics, history, public policy, and presidential transitions convened by The Center for American Progress.

In 1977, Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)[5] to ensure that federally insured depository institutions were granting credit in communities where they collected deposits. Along with the Fair Housing Act, this law is the primary legislation created to end redlining. This legislation addresses how banks serve the credit needs of low-to-moderate income (LMI) neighborhoods, as the federal regulators judge performance. Compliance with the CRA is necessary for the banks to apply for new charters, branches, mergers, and acquisitions. Banks are graded on three examination tests: lending, investments, and service. Critics argue that as the primary legislation to end redlining and ensure inclusive finance from banks, CRA enforcement is neither effective nor sufficient. Critics further say that The CRA lacks lending quotas or benchmarks, and nearly every bank receives at least satisfactory ratings by the federal regulators, indicative of weak enforcement.

One of the primary ways large banks fulfill CRA requirements are with investments in Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). [TSW1] CDFIs[6] are mission driven, financial institutions certified by the US Treasury’s CDFI Fund and are designated to provide credit and financial services to LMI individuals and historically disadvantaged communities. Most Minority Depository Institutions (MDIs) are also CDFIs. In fact, some may argue that MDIs are the original CDFIs given they were created to serve underserved communities of color. CDFIs must direct at least 60% of their financing towards LMI or underserved communities. CDFIs rely on investments from larger commercial banks to provide loans. However, the need for alternative lenders such as CDFIs is evidence of a larger problem—large commercial banks do not meet the credit needs of the LMI neighborhoods that their branches serve. Be it because of lack of financial incentive or the perpetuation of discriminatory policies, this market failure continues to exist.

Banks may not lend in Black neighborhoods because they fail to see their value. Research by Andre Perry, Senior Fellow of the Brookings Institution, illustrates that homes of similar quality in majority Black neighborhoods are worth 23% less [7] than their white counterparts, even when controlling for common appraisal criteria such as education, amenities, and crime. Across Black majority neighborhoods, owner-occupied homes are undervalued by $48,000 per home on average, amounting to a cumulative loss in wealth of $156 billion dollars nationwide. This systematic devaluation of Black assets provides evidence that the appraisal methods that banks use have a bias against Black communities.

This bias in appraisals results in lack of credit access. Larger commercial banks by and large do not make small dollar mortgages. The Urban Institute released a report [8]on the small dollar mortgage problem, where banks fail to make loans under a certain value. For the purposes of their report, the Urban Institute chose $70,000 as the threshold for small dollar mortgages. For properties valued at $70,000 or less, only 25% of purchases were financed with a traditional mortgage loan product. White homes, valued between $70,000 and $150,000, had nearly 80% financed with a traditional mortgage product. The lack of financing for low-priced homes underscores the challenges and lack of support that LMI individuals may face when home-buying.

This phenomenon is more consequential with a bird’s eye view. Detroit, for example, the nation’s largest majority-Black city. The city of approximately 700,000 people only had around 1,700 mortgages in 2019, with less than a quarter of home purchases financed using traditional mortgage loans. The view gets even more stark when emphasizing racial equity. Detroit’s population is made up of around 80% African American residents, but in 2017, Black applicants had almost the same number of mortgages as white borrowers, who only make up less than 15% of the population. In 2020, African American applicants were denied home purchase loans at twice the rate as white applicants, and some were denied despite having a higher income than approved white applicants.

Black-owned banks have provided financial support to the Black community, especially when the market does not. The Milken Institute reports that on average 70% of minorities do not have a branch in their neighborhood and at the same time, MDI branches are located in census tracts with an average 77% minority population compared to 31% for all FDIC-insured depository institutions. Black banks are anchored in Black cities or regions and have a strong record of lending in Black neighborhoods to Black borrowers. According to Urban Institute, the share of mortgage originations to Black borrowers ranges from 75% and 100%[9] of borrowers at Black Banks, while the share of Black borrowers at other types of banks never exceeds 10%. When considering an applicant, Black banks take a more comprehensive approach, taking other factors into consideration rather than a typical credit profile, a practice known as relationship banking.

As bank branches and headquarters are located within the neighborhoods and cities that they lend within, Black banks apply context and community knowledge to lending decisions. Because of this holistic approach to lending, Black banks also provide countercyclical credit access, providing greater access when markets retract, as evidenced by their performance during the Great Recession. Black banks are community banks. The FDIC defines a community bank as banks with less than $10 billion in assets[10], a category all Black banks fall under. Community banks tend to have a narrower focus and use their deposits to support their primary revenue source of lending within their community. Black banks also tend to be CDFIs, making up the largest contingent of Minority Depository Institutions (MDI) CDFIs at 56%.

Community banks, CDFIs, MDIs, and Black banks make the loans that larger banks typically do not. Large banks, who serve an enlarged proximity, have a wide array of operations and use their deposits for financial products other than typical community reinvestment. Deposits made in large banks often leave the community from which it came, removing the primary role banks are supposed to play – cycling money through a local economy. Taking this one step further, communities served by larger banks may have more trouble getting loans from banks who have other profit-generating operations, and as such, may suffer. Research by Erik Mayer Ph.D, Assistant Professor of Finance at SMU Cox, found exactly that. Communities served by larger banks have reduced access to credit[11], leading to less economic mobility than communities served by locally-based financial institutions. According to Mayer, as large banks significantly increase their market share in an area, by a standard deviation, upward mobility levels fall by nearly 5%.

Banks have been consolidating for decades, as federal and state regulations have made it easier for larger banks to acquire smaller banks and competition has made it more difficult for small banks to survive. This trend is also true for Black banks. At their height, there were 134 Black-owned banks in the United States. Today, only 19 exist. By comparison, as of February 2021, there were 10,605 financial technology startups in North America, up from 5,800 in 2019. The advantages of Black banks are clear, yet greater public action to support these institutions is still necessary. Several government policies have been crafted since the 1970s to support Black and minority depository institutions, more familiar ones such as the CRA and the CDFI Fund and newer ones like the Community Development Capital Initiative (CDCI) and Emergency Capital Investment Program (ECIP). In 2008 the US Treasury created (CDCI), where the government helped to recapitalize CDFIs through the purchase of preferred equity stakes. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, created the ECIP that incentivized, through capitalization, LMI community financial institutions to support small businesses and consumers in their respective communities.

“The ECIP program gives us [Black Banks] more capital than we currently have. It is a significant capital building program for our institutions. Because of that the future looks absolutely brilliant. In the next three to five years you should see most Black-owned banks double in size.” – B. Doyle Mitchell Jr. Industrial Bank President and CEO Still, the evidence is clear that these banks, which provide a unique service critical to the equitable development for disadvantaged populations, need and deserve much greater support.

[1] Gross, T (2017). A ‘Forgotten History’ Of How The U.S. Government Segregated America. NPR. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://www.npr.org/2017/05/03/526655831/a-forgotten-history-of-how-the-u-s-government-segregated-america

[2] Best, R, MejÍa, E (2022). The Lasting Legacy Of Redlining. FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/redlining/

[3] All Things Considered (2017). ‘The Color Of Law’ Details How U.S Housing Policies Created Segregation. NPR. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://www.npr.org/2017/05/17/528822128/the-color-of-law-details-how-u-s-housing-policies-created-segregation

[4] Weller, C, Roberts, L (2021). Eliminating the Black-White Wealth Gap Is a Generation Challenge. CAP. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/eliminating-black-white-wealth-gap-generational-challenge/

[5] NCRC https://ncrc.org/treasureCRA/

[6] Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) and Community Development (CD) Bank Resource Directory https://www.occ.gov/topics/consumers-and-communities/community-affairs/resource-directories/cdfi-and-cd-bank/index-cdfi-and-cd-bank-resource-directory.html

[7] Perry, A , Rothwell, J , Harshbarger, D (2018) The devaluation of assets in Black neighborhoods. Brookings. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://www.brookings.edu/research/devaluation-of-assets-in-black-neighborhoods/#:~:text=Homes%20of%20similar%20quality%20in,few%20or%20no%20Black%20residents

[8] Zhu, L , Ballesteros, R (2021) Making FHA Small-Dollar Mortgages More Accessible Could Make Homeownership More Equitable. Urban Institute. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/making-fha-small-dollar-mortgages-more-accessible-could-make-homeownership-more-equitable

[9] Neal, M , Walsh, J (2020) The Potential and Limits of Black-Owned Banks. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101849/the20potential20and20limits20of20black-owned20banks.pdf

[10] FDIC Community Banking Study (2012) Chapter 1 – Defining the Community Bank. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://www.fdic.gov/resources/community-banking/report/2012/2012-cbi-study-1.pdf

[11] Warren, J (2020) Larger banks Lead to Less Economic Mobility. SMU Cox. Retrieved on August 30, 2022 from https://www.smu.edu/cox/Learning-Culture/Research-Papers/20200201_Erik-Mayer